Moon's Mysterious 'Ocean of Storms' Explained

The largest dark spot on the moon, known as the Ocean of Storms, may be a scar from a giant cosmic impact that created a magma sea more than a thousand miles wide and several hundred miles deep, researchers say.

These findings could help explain why the moon's near and far sides are so very different from one another, investigators added.

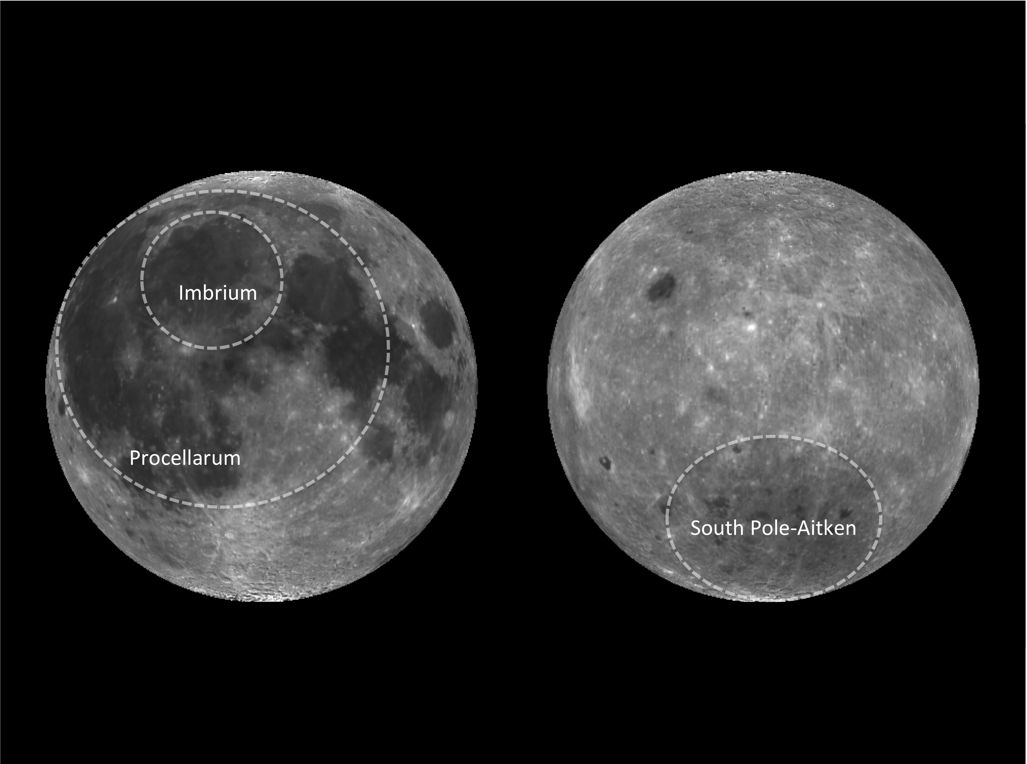

Scientists analyzed Oceanus Procellarum, or the Ocean of Storms, a dark spot on the near side of the moon more than 1,800 miles (3,000 kilometers) wide.

The near side of the moon, the side that always faces Earth, is quite different from the far side, often erroneously called the moon's dark side (this side does in fact get sunlight — it simply never faces Earth). For example, widespread plains of volcanic rock called "maria" (Latin for seas) cover nearly a third of the near side, but only a few maria are seen on the far one.

Researchers have posed a number of explanations for the vast disparity between the moon's near and far sides. Some have suggested that a tiny second moon may once have orbited Earth before catastrophically slamming into the other moon, spreading its remains mostly on the moon's far side. Others have proposed that Earth's pull on the moon caused distortions that were later frozen in place on the moon's near side.

Similarly, Mars' northern and southern halves are also stark contrasts from one another, and researchers had suggested that a monstrous impact may have been the cause. Now scientists in Japan say that a giant collision may also explain the moon's two-faced nature, one that gave rise to the Ocean of Storms.

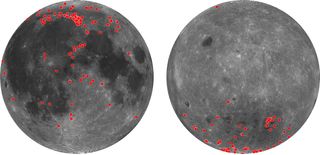

The researchers analyzed the composition of the moon's surface using data from the Japanese lunar orbiter Kaguya/Selene. These data revealed that a low-calcium variety of the mineral pyroxene is concentrated around Oceanus Procellarum and large impact craters such as the South Pole-Aitkenand Imbriumbasins. This type of pyroxene is linked with the melting and excavation of material from the lunar mantle, and suggests the Ocean of Storms is a leftover from a cataclysmic impact.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

This collision would have generated "a 3,000-kilometer (1,800-mile) wide magma sea several hundred kilometers in depth," lead study author Ryosuke Nakamura, a planetary scientist at the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology in Tsukuba, Japan, told SPACE.com.

The investigators say that collisions large enough to create Oceanus Procellarum and the moon's other giant impact basins would have completely stripped the original crust on the near side of the moon. The crust that later formed there from the molten rock left after these impacts would differ dramatically from that on the far side, explaining why these halves are so distinct.

Some researchers had speculated that the Procellarum basin was the relic of a gigantic impact. However, this idea was hotly debated because there were no definite topographic signs it was an impact basin, "possibly because the formation date was too old, maybe more than 4 billion years," Nakamura said. "Our discovery provides the first compositional evidence of this idea, which could be confirmed by future lunar sample return missions, such as Moonrise," a proposed NASA mission that would send an unmanned probe to collect lunar dirt and return it to Earth.

"The neighboring Earth likely experienced similar-sized impacts around the same period," Nakamura added. "It would have had a great effect on the onset of Earth's continental crust formation and the beginning of life."

The scientists detailed their findings online Oct. 28 in the journal Nature Geoscience.

Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us